Tiny wood-eating marine creatures, called gribbles, could be the key to a sustainable model for the conversion of wood into green energy.

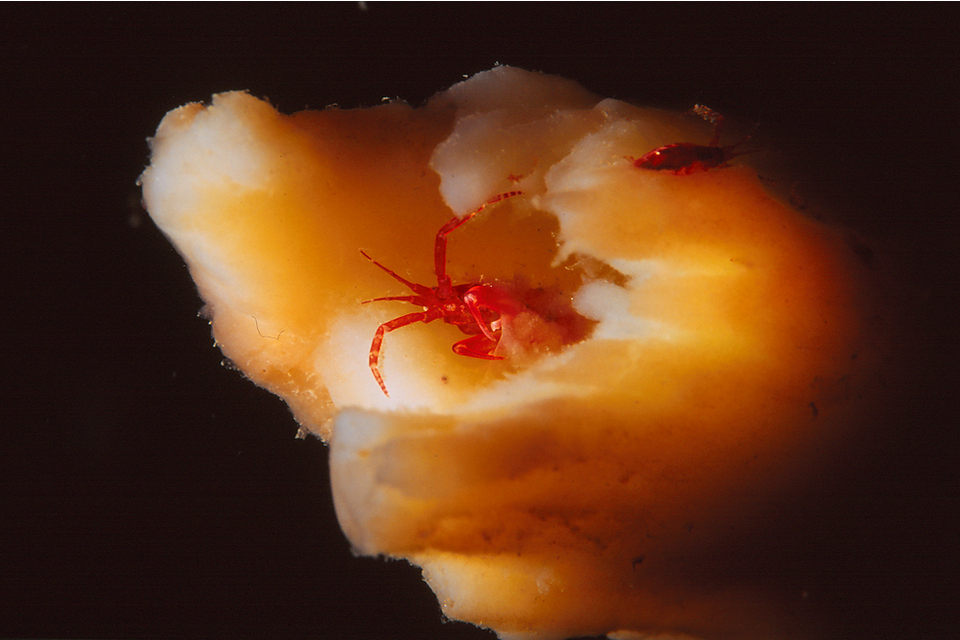

Gribbles, or Limnoriidae, are a family of over fifty species of tiny marine crustaceans.

Living in colonies, some gribbles species are xylophagous, meaning their diet consists of mainly wood and plant material.

In the marine ecosystem, these minute invertebrates play an important role in the recycling of wood junk, rich in lignin and cellulose, which washes into the ocean.

As such, gribble worms also present a serious threat as they can chomp on the wood of boats, piers, and docks.

Wood-boring gribble species, known as Limnoria lignorum, have a unique digestive system that enables them to extract the sugars hidden inside wood.

New research reveals that this system could help us develop efficient wood to biofuel conversion processes.

Gribbles Recipe for Wood Biofuel

To get their food, gribbles have to break through lignin, the tough organic polymer that coats wood sugars.

How exactly do these pale little pests do that, especially as they don’t rely on any microbes to assist them?

Biologists at York University (UK) led a research that set out to answer this question.

They investigated gribbles’ wood-digesting ability and how it would help in the development of efficient and cheap wood-to-biofuel conversion.

The team found that gribbles amazing mechanism comes down to proteins, namely hemocyanins.

Researchers who studied the “hindgut” of gribbles, found that hemocyanins “are crucial to their ability to extract sugars from wood.”

Hemocyanin to invertebrates is what hemoglobin is for humans and animals. It’s hemocyanin that carries oxygen in the blood of invertebrates.

Read More: New Jet Biofuels Take to the Sky

While hemoglobin uses iron atoms to bind oxygen, hemocyanins binds oxygen through its association with copper atoms. This causes the blood of invertebrates like gribbles to have a blue color.

These species “have harnessed the oxidative capabilities of hemocyanins to attack the lignin bonds that hold the wood together.”

What interests biologists in gribbles is their “sterile” digestive system. Unlike other wood-digesting animals, like termites, gribbles don’t have to call on bacteria to do the job.

“We found that gribbles first chew wood into very small pieces before using hemocyanins to disrupt the structure of lignin. GH7 enzymes, the same group of enzymes used by fungi to decompose wood, are then able to break through and release sugars,” said York’s biology professor Simon McQueen-Mason.

Just like gribbles, pretreatment of wood for biofuel extraction is a standard industrial process that uses thermochemicals instead of proteins.

In the lab, researchers tested hemocyanins on wood and the samples treated yielded twice as many sugars compared to regular industrial chemicals.

As researchers note, “woody plant biomass is the most abundant renewable carbon resource on the planet, and, unlike using food crops to make biofuels, its use doesn’t come into conflict with global food security… In the long term this discovery may be useful in reducing the amount of energy required for pre-treating wood to convert it to biofuel.”

Comments (0)

Most Recent