Since being predicted by Einstein’s General Relativity theory, black holes seemed to get even more and more mysterious as the collective astrophysical mind kept investigating them.

Although scientists have accumulated significant theoretical and experimental literature about black holes, until recently, they couldn’t see what they really look alike.

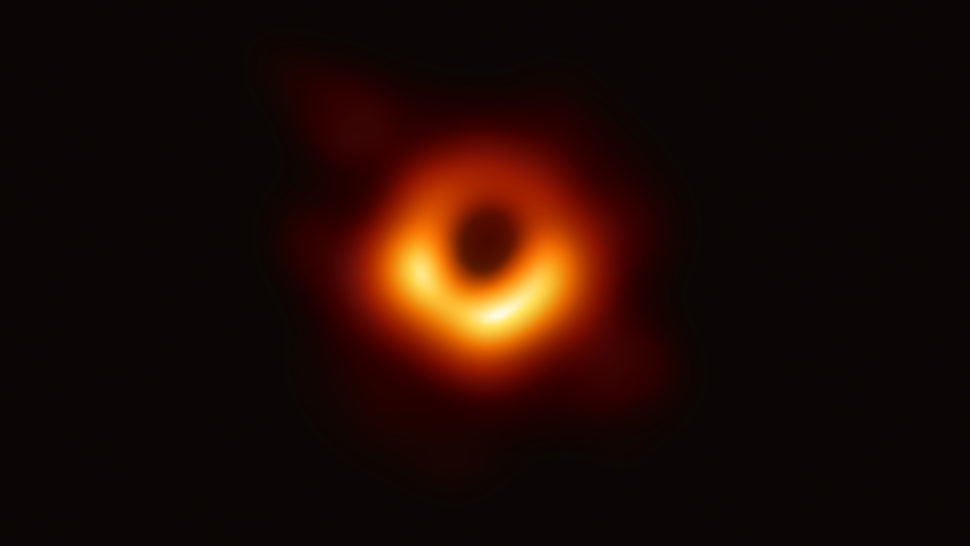

Digital simulations and artist renditions may show us more about black holes, and they do get a lot right, but they don’t do our curiosity justice like a real image does, no matter how blurry it is.

Now, it’s done!

It took a dozen years, hundreds of scientists, and an Earth-sized telescope, but now, we have our first real image of a black hole.

We Saw the Unseeable

In 2006, an international team of more than 200 researchers, led by Harvard University astronomers, launched the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) project with a sole aim: to capture a direct shot of a black hole.

Fast forward over thirteen years, and they can finally say mission accomplished.

Wednesday, April 10, the EHT team held coordinated press conferences around the world to unveil the first real photo of a black hole.

Much like what theories and computer models predicted, the photo reveals a ring-like glowing structure surrounding a central dark region, or the black hole.

“We are delighted to be able to report to you today that we have seen what we thought was unseeable. We have seen and taken a picture of a black hole,” said Harvard’s Shep Doeleman, EHT Director.

In the picture, we don’t see the black hole itself, but rather a silhouette. Light photons that would have enabled us to see get gobbled up with the surrounding matter by the black hole and never get past the event horizon.

And that’s what we really see here, the black hole’s shadow limited by the event horizon, that is, the point of no return.

Why it’s not our own Sagittarius A* in the Picture?

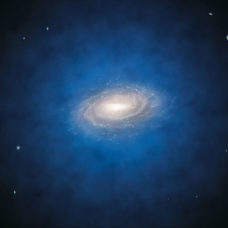

Churning away at the center of the Milky Way is Sagittarius A*, a black hole that’s about 4.3 million times the mass of our sun.

Don’t get me wrong, our Sgr A* is a large black hole but compared to other supermassive baddies out there in the Universe, it gets dwarfed to the point it looks like a tiny donut.

About 55 million light-years away from Earth, in a galaxy called Messier 87, lurks an ultramassive black hole (M87*) whose mass is equivalent to 6.5 billion solar masses.

It’s M87 * in the photo released by the EHT team.

Why didn’t they target the black hole sitting in the center of our own galaxy?

As supermassive as Sagittarius A* is, it’s hard to be viewed from Earth.

“Supermassive black holes are relatively tiny astronomical objects — which has made them impossible to directly observe until now. As a black hole’s size is proportional to its mass, the more massive a black hole, the larger the shadow. Thanks to its enormous mass and relative proximity, M87’s black hole was predicted to be one of the largest viewable from Earth — making it a perfect target for the EHT”.

Read More: Scientists Take Extraordinary New Photos of the Milky Way Core

No matter which black hole is pictured, this feat can help astrophysicists assess their theories, adjust their models, and improve their overall understanding of black holes.

“Even though those processes are things that could happen, we have not seen any of them happening in front of our eyes to be able to understand it,” Dimitrios Psaltis, an EHT project scientist told The Verge, before the release of the photo, “by taking a picture very, very close to the event horizon, we can now start exploring our theories of what happens when I throw matter onto a black hole.”

The Event Horizon Telescope: What Took Them so Long to get the Picture?

We got this breakthrough image thanks to the Event Horizon Telescope that’s like no other.

The EHT is a network of 8 radio telescopes distributed over the planet to form a virtual telescope that’s 6,200 miles in diameter, about as large as Earth itself. They basically used all available submillimeter telescopes in the world.

They didn’t just get the data flowing right away. They had to connect these telescopes and fit them with upgraded equipment to boost the EHT’s sensitivity and resolution capacity.

This took a couple of years before data started flowing in. Gathering data to construct the photo took another two years.

Enormous amounts of raw data had to be collected and analyzed, which is a lot easier said than done. Each telescope in the EHT network generated about 1 petabyte of data each observing night. So, to transfer data files, the internet wasn’t an option. Instead, the team relied on the good old way, by mailing hard disks, in this case, a faster method than the Internet.

“We have achieved something presumed to be impossible just a generation ago. Breakthroughs in technology, connections between the world’s best radio observatories, and innovative algorithms all came together to open an entirely new window on black holes and the event horizon,” said the EHT director.

Black holes are very interesting things. Is there a possibility of time travel if spaceships can revolve around black holes?