More and more, researchers from all walks of science seem to be inspired by biological and natural processes. A team of researchers from the University of Cambridge and the Beijing Institute of Technology has developed a more efficient lithium-sulfur (Li-S) battery by studying the human small intestine.

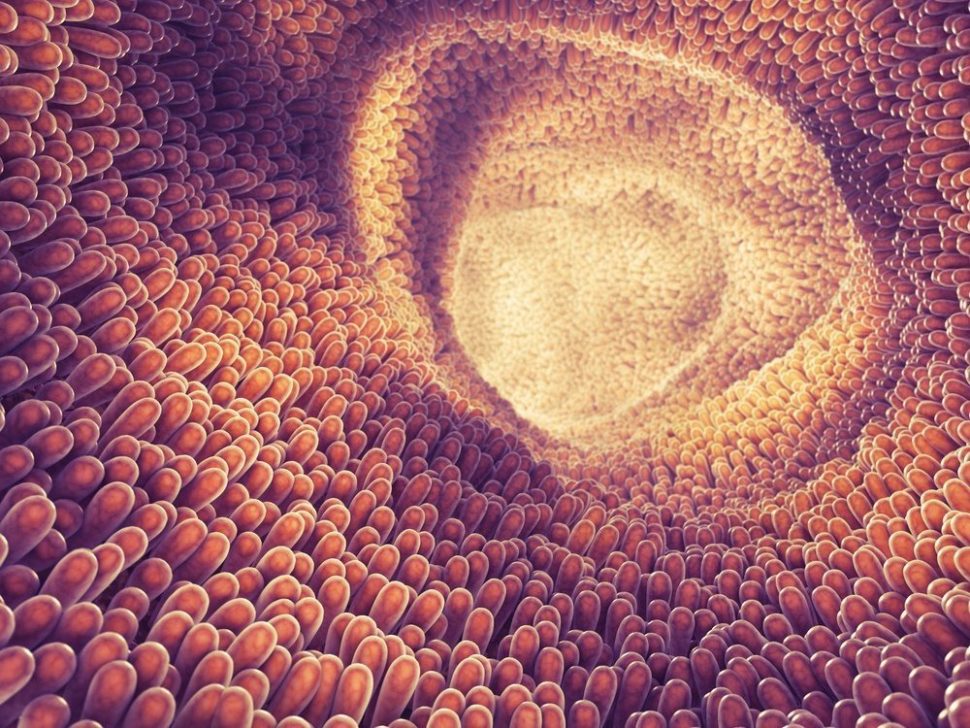

The new battery uses a lightweight nanostructured material similar to villi. These microscopic, finger-like structures on the lining of the small intestine are tasked with absorbing nutrients from the food that we eat.

This intestine-inspired battery’s “villi”, however, are made of tiny zinc oxide wires that function using a kind of re-uptake. As active electrochemical materials dissolve from the electrode after a discharge cycle, the artificial villi trap them. Then, the villi absorb the materials, thereby allowing these previously discarded solutes to be reused.

Limits of Conventional Batteries

The Li-S battery is a high-density rechargeable battery that, when compared to the commonly used lithium-ion battery, is a lighter and more energy dense power source with up to 1,500 charge and discharge cycles.

There are, however, a few drawbacks to Li–S batteries.

For instance, after a number of charge-discharge cycles, the electrode is depleted of sulfur molecules and cannot be reused.

Sulfur’s low boiling point also makes Li–S batteries unsafe when exposed to high temperatures.

The practical challenges of working with Li–S batteries spurred researcher’s innovative spirit. In 2015, researchers from the University of Waterloo in Canada and BASF SE in Germany developed a method of preventing disintegrating sulfur from leaving the battery.

Thin sheets of manganese dioxide react with sulfur to form compounds that chemically bond with polysulfides and effectively trap the materials inside the battery where they are available for reuse.

“Changing from stiff nickel foam to flexible carbon fiber mat makes the layer mimic the way the small intestine works even further,” – Yingjun Liu.

The Intestine-Inspired Battery

The Cambridge researchers also used a functional layer over the cathode to give the trapped active material a conductive network in which to be reused. The layer is made up of tiny zinc oxide nanowires and uses nickel foam for support. The nickel foam was later replaced with carbon fiber to reduce the battery’s weight.

“Changing from stiff nickel foam to flexible carbon fiber mat makes the layer mimic the way the small intestine works even further,” explained collaborating researcher Yingjun Liu.

The intestine-inspired battery findings offer a practical and highly efficient fix for the Li–S battery. Despite these advances, they are only a proof of concept. While the findings are encouraging for shaping efficient and circular economies, commercially viable Li-S batteries are still in the not-too-distant future.

Comments (0)

Most Recent