It’s a bit ironic that we can’t detect, much less see, most of what we call the “Observable Universe”.

Among the long-standing mysteries in physics is dark matter that’s been puzzling astronomers for decades.

So far, all attempts at spotting dark matter’s elusive particle, including experiments at the Large Hadron Collider, have failed.

While dark matter’s large-scale effects on the fabric of space-time are salient, one of the burning questions is its origin. Where could it come from?

In the debate around dark matter, there’s one scientist’s name that’s unavoidable: Stephen Hawking.

The late physicist — who spent his life finding answers to such big questions — has a famous theory about the origin of dark matter that brings up another mysterious, albeit more familiar, phenomenon in the universe: black holes.

Now, researchers claim they have debunked Hawking’s theory.

Dark Matter and Primordial Black Holes

Based on their mass, black holes are classified into stellar, intermediate, and supermassive categories.

Basically, all these kinds of black holes follow the same formation process that involves the explosion of a giant star — the bigger the star, the more massive its black hole offshoot.

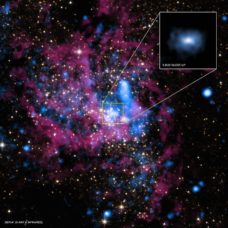

Then, unless it’s a supermassive monster sitting at the center of the galaxy, like ours, a black hole would roam around space, getting bigger as it devours surrounding matter.

But in 1974, Stephen Hawking hypothesized the existence of a fourth type: tiny black holes that formed at the beginning of the universe. He suggested that these Primordial Black Holes (PBHs) could make up all or most of dark matter.

Primordial Black Holes wouldn’t have formed from the collapse of stars because back then, right after the Big Bang, stars hadn’t yet had the time to form themselves.

Clouds of gas would’ve clumped together and coalesced into an abundance of minute black holes smaller than a tenth of a millimeter.

Read More: What Dark Matter and Primordial Black Holes Might Have in Common

Recently, simulations run by researchers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics gave some credence to Hawking’s theory.

But no matter how elaborate a theory or a simulation is, they have little chance of standing against contradicting hard observation data.

Astronomers, from Japan, India and the US, closed in on our neighbor galaxy Andromeda using the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii to put Hawking’s theory on primordial black holes and dark matter to its “most rigorous test to date”.

We Finally Know What 0.1 Percent of Dark Matter Is

The team looked for primordial black holes that would lie between Earth and the Andromeda galaxy through the gravitational lensing effect, or how they would bend distant light coming to us.

But it’d be hard to find a star in Andromeda that lines perfectly with a primordial black hole, acting as a gravitational lens, and an observer here on Earth.

So, researchers turned to the Subaru telescope and its state-of-the-art Hyper Suprime-Cam digital camera that “can capture the whole image of the Andromeda galaxy in one shot”.

The findings of the study, published in the Nature Astronomy journal, rule out the possibility that minuscule primordial black holes make up most of dark matter.

During one night, and over seven hours, the team took 190 consecutive images of Andromeda and analyzed the data expecting to find about 1000 gravitational lensing events.

However, they could only “identify one case” leading them to conclude that primordial black holes make up no more than “0.1 percent of all dark matter mass. Therefore, it is unlikely the theory is true”.

These results show that Hawking wasn’t entirely wrong about dark matter’s nature. Now at least we know what 0.1 percent of dark matter is, or a tiny part of the mystery finally elucidated. Astrophysicists now have to figure out what makes up the remaining 99.99 percent of dark matter.

minuscule*