A team of engineers has developed 3D-printed devices that can track and store how they are used.

The same team of engineers who made headlines last year for their 3D-printed devices that can connect to WiFi without batteries or electronics is now back with their latest invention. This time, they developed another set of 3D-printed objects that can track and store their use, again without any batteries or electronics attached to it.

“We’re interested in making accessible assistive technology with 3D printing, but we have no easy way to know how people are using it,” Jennifer Mankoff, one of the team’s researchers and a professor at the University of Washington’s Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering, said.

“Could we come up with a circuitless solution that could be printed on consumer-grade, off-the-shelf printers and allow the device itself to collect information? That’s what we showed was possible in this paper.”

The 3D-printed objects use mechanical features to track their use. They also utilize the backscatter method to share the information they have gathered with other devices. The researchers believe that their latest innovation could help in monitoring patients under medication and those who use prosthetics.

The team used two antennas which can signal movement in two directions in their new objects, an upgrade from their previous invention which only tracks one movement in one direction using a gear.

“Last time, we had a gear that turned in one direction. As liquid flowed through the gear, it would push a switch down to contact the antenna,” Vikram Iyer, a doctoral student in the UW Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering and lead author of the study, said.

The antennas were placed on top and at the bottom of the pill bottle that they invented. In those positions, the antennas can contact the switch attached to a gear.

“So opening a pill bottle cap moves the gear in one direction, which pushes the switch to contact one of the two antennas. And then closing the pill bottle cap turns the gear in the opposite direction, and the switch hits the other antenna,” Iyer added.

Justin Chan, co-author of the study explained that the “gear’s teeth have a specific sequencing that encodes a message” like Morse Code. Turning the cap in one direction will enable a person to see the message. But, turning it in the reverse direction will also reverse the message.

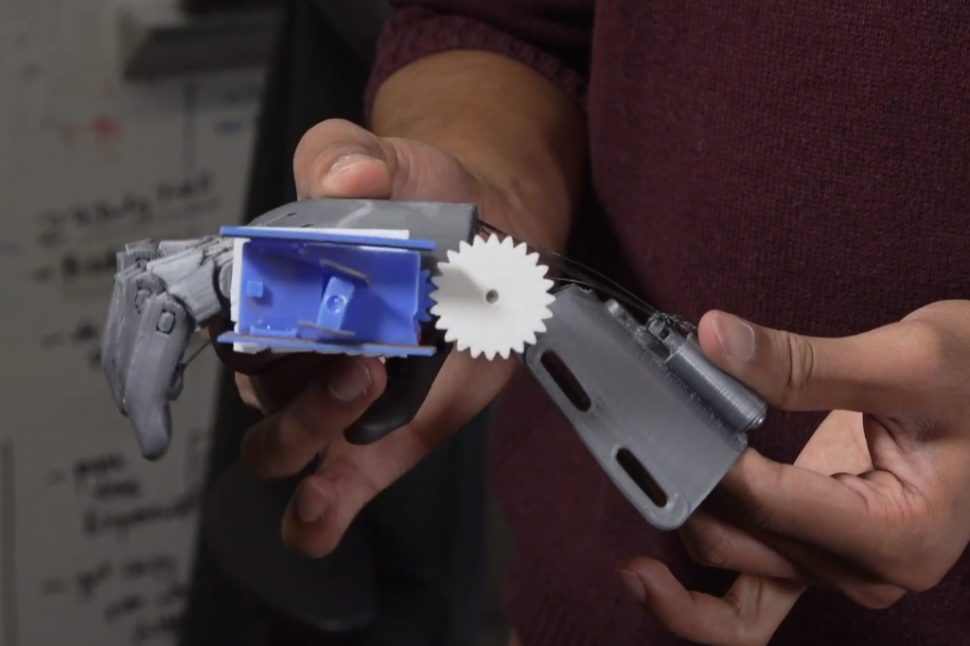

Aside from tracking a pill bottle’s cap movement, the technology can also be used to monitor 3D prosthetics like the e-NABLE arms.

The team 3D-printed the arm then attached a prototype of their bidirectional sensor to it. The sensors allowed the researchers to monitor the hand’s opening and closing through the wrist angle.

“This system will give us a higher-fidelity picture of what is going on,” Mankoff said. “For example, right now we don’t have a way of tracking if and how people are using e-NABLE hands. Ultimately what I’d like to do with these data is predict whether or not people are going to abandon a device based on how they’re using it.”

Iker and his team will be presenting their work at the ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology in Germany.

Do gadgets always share all data they collect or do they hide something even from their owners for the manufacturer’s aims? In such cases there might be demand for open data adapters.